This past fall I participated in Amazing Grace: How Writers Helped End Slavery, a masters level course offered by the Gilder-Lehrman Institute of American History. The course, led by Columbia Professor, and GLI President, James Basker, examined the role of abolitionist writers in the 19th century struggle to end that "peculiar institution." The final project was to compile our own abolitionist writing anthology that could be used in the classroom.

I wanted to share the work I generated during this course as perhaps the primary sources I chose could prove useful in your own classrooms. In this blog "mini-series" (Amazing Grace) I will share with you my reflections, my anthology introductions, and the sources themselves. Most, if not all, of the sources I reference can be found in James Basker's book American Antislavery Writings: Colonial Beginnings to Emancipation.

I wanted to share the work I generated during this course as perhaps the primary sources I chose could prove useful in your own classrooms. In this blog "mini-series" (Amazing Grace) I will share with you my reflections, my anthology introductions, and the sources themselves. Most, if not all, of the sources I reference can be found in James Basker's book American Antislavery Writings: Colonial Beginnings to Emancipation.

Patrick Henry, Letter to John Alsop, 1773

Reflection:

One of the major themes and discussion questions that runs throughout my 7th grade American History class is: How have we become a more perfect union? Taken from the Constitution and used as a mission statement for our nation, my students measure the successes and failures of our democratic experiment. The hardest part of introducing this theme to a group of predominantly African American teenagers is the inherent and obvious hypocrisies that existed in the colonial and revolutionary eras. To this end, I found the Patrick Henry letter, Letter to John Alsop, from January 13th, 1773, to be an incredibly unique and insightful document for inclusion in my classroom.

Henry is refreshingly candid and open in this letter, not just outlining his practical beliefs on slavery but also clearly and freely admitting to failing to put his ideas into practice. His blunt reflection will be particularly accessible to my middle school students in that they too can relate to believing in one ideal but finding it hard to put that into practice – whether for “general inconvenience” or peer pressure.

What I found to be the most significant thing about Henry’s letter was the perspective. He, who was a vocal patriot, could speak of the virtues of liberty and independence but at the same time felt incapable – or perhaps more to the point, unwilling – to extend those ideals to the enslaved Africans. Could he not see clear analogy of the founders and slaves and the king and the colonists? How the king’s tyranny in taxes was in fact less a transgression than the colonists’ tyranny over the body and souls of enslaved peoples? This letter helps to frame two important discussion questions that I engage my students in at this time of study: 1. Did framers consider or debate the extension of rights to more than just white males, and 2. Is there to be sympathy to the king and parliament in the taxation debate?

This letter clearly lets my junior historians in on the thought process of how slavery fits into the Enlightened/Revolutionary Era, while also perhaps providing some insight and perspective on how King George might have viewed the colonists.

One of the major themes and discussion questions that runs throughout my 7th grade American History class is: How have we become a more perfect union? Taken from the Constitution and used as a mission statement for our nation, my students measure the successes and failures of our democratic experiment. The hardest part of introducing this theme to a group of predominantly African American teenagers is the inherent and obvious hypocrisies that existed in the colonial and revolutionary eras. To this end, I found the Patrick Henry letter, Letter to John Alsop, from January 13th, 1773, to be an incredibly unique and insightful document for inclusion in my classroom.

Henry is refreshingly candid and open in this letter, not just outlining his practical beliefs on slavery but also clearly and freely admitting to failing to put his ideas into practice. His blunt reflection will be particularly accessible to my middle school students in that they too can relate to believing in one ideal but finding it hard to put that into practice – whether for “general inconvenience” or peer pressure.

What I found to be the most significant thing about Henry’s letter was the perspective. He, who was a vocal patriot, could speak of the virtues of liberty and independence but at the same time felt incapable – or perhaps more to the point, unwilling – to extend those ideals to the enslaved Africans. Could he not see clear analogy of the founders and slaves and the king and the colonists? How the king’s tyranny in taxes was in fact less a transgression than the colonists’ tyranny over the body and souls of enslaved peoples? This letter helps to frame two important discussion questions that I engage my students in at this time of study: 1. Did framers consider or debate the extension of rights to more than just white males, and 2. Is there to be sympathy to the king and parliament in the taxation debate?

This letter clearly lets my junior historians in on the thought process of how slavery fits into the Enlightened/Revolutionary Era, while also perhaps providing some insight and perspective on how King George might have viewed the colonists.

Introduction:

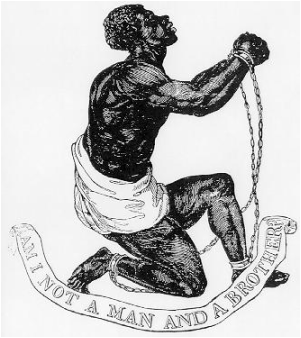

Though this anthology will examine the abolitionist writings of the 19th century, it is helpful for our purposes to understand that the issue of slavery existed concurrently with the movement for independence in the United States in the 1770s. This letter, written by the Virginian attorney and politician, Patrick Henry, speaks to the hypocrisy inherent in the independence movement that sought to unshackle the colonists from the tyrannical and oppressive King George III but also strove to keep intact the burgeoning institution of slavery. Henry, the same man who proudly proclaimed “Give me liberty or give me death,” is writing to his Quaker friend, John Alsop relating his personal account of slavery. The Quakers were among the first groups to speak out publicly against the institution of slavery, signing a denunciation of the practice in 1688 upon the founding of Germantown, Pennsylvania. Henry refers to a book by Anthony Benezet, a Quaker leader who pushed for his society to break all ties with slavery in his work in the 1740s and 1750s.

As you investigate the letter excerpt, consider the following questions:

Though this anthology will examine the abolitionist writings of the 19th century, it is helpful for our purposes to understand that the issue of slavery existed concurrently with the movement for independence in the United States in the 1770s. This letter, written by the Virginian attorney and politician, Patrick Henry, speaks to the hypocrisy inherent in the independence movement that sought to unshackle the colonists from the tyrannical and oppressive King George III but also strove to keep intact the burgeoning institution of slavery. Henry, the same man who proudly proclaimed “Give me liberty or give me death,” is writing to his Quaker friend, John Alsop relating his personal account of slavery. The Quakers were among the first groups to speak out publicly against the institution of slavery, signing a denunciation of the practice in 1688 upon the founding of Germantown, Pennsylvania. Henry refers to a book by Anthony Benezet, a Quaker leader who pushed for his society to break all ties with slavery in his work in the 1740s and 1750s.

As you investigate the letter excerpt, consider the following questions:

- What does Patrick Henry state as his personal opinions on the institution of slavery?

- How does Henry justify the continuation of slavery in spite of those beliefs?

- How might Henry’s explanation provide an opportunity for the patriots to empathize with enslaved Africans?

- How might this letter expose hypocrisies in the movement for independence and in the Declaration of Independence?

Source:

HANOVER, Va., Jan. 13, 1773.

DEAR SIR: I take this opportunity to acknowledge the receipt of ANTHONY BENEZETS book against the Slave trade. I thank you for it. It is not a little surprising that Christianity, whose chief excellence consists in softening the human heart, in cherishing and improving its finer feelings, should encourage a practice so totally repugnant to the first impressions of right and wrong. What adds to the wonder is that this abominable practice has been introduced in the most enlightened ages. Times that seem to have pretensions to boast of high improvements in arts, sciences and refined morality, have brought into general use and guarded by many laws a species of violence and tyranny which our more rude and barbarous, but more honest ancestors detested.

Is it not amazing that at a time when the rights of humanity are defined and understood with precision, in a country, above all others, fond of liberty -- that in such an age and such a country we find men professing a religion the most humane, mild, meek, gentle and generous, adopting a principle as repugnant to humanity as it is inconsistent with the Bible and destructive to liberty? Every thinking, honest man rejects it in speculation. How few, in practice, from conscientious motives!

The world, in general, has denied your people a share of its honors; but the wise will ascribe to you a just tribute of virtuous praise for the practice of a train of virtues, among which your disagreement to Slavery will be principally ranked. I cannot out wish well to a people whose system imitate the example of Him whose life was perfect; and, believe me, I shall honor the Quakers for their noble efforts to abolish Slavery. It is equally calculated to promote moral and political good.

Would any one believe that I am master of slaves by my own purchase? I am drawn along by the general inconvenience of living without them. I will not -- I cannot justify it, however culpable my conduct. I will so far pay my devoir to Virtue, as to own the excellence and rectitude of her precepts, and to lament my want of conformity to them. I believe a time will come when an opportunity will be afforded to abolish this lamentable evil. Everything we cam do, is to improve it, if It happens in our day; if not, let us transmit to our descendants, together with our slaves, a pity for their unhappy lot, and an abhorrence of Slavery. If we cannot reduce this wished-for reformation to practice, let us treat the unhappy victims with lenity. It is the furthest advancement we can make toward justice. It is a debt we owe to the purity of our religion, to show that it is at variance with that law which warrants Slavery.

Here is an instance that silent meetings (the scoff of reverend doctors) have done that which learned and elaborate preaching cannot effect; so much preferable are the general dictates of conscience, and a steady attention to its feelings, above the teachings of those men who pretend to have found a better guide. I exhort you to persevere in so worthy a resolution, Some of your people disagree, or at least are lukewarm in the Abolition of Slavery. Many treat the resolution of your meeting with ridicule; and among those who throw ridicule and contempt on it are clergymen whose surest guard against both ridicule and contempt, is a certain act of Assembly.

I know not where to stop. I could say many things on this subject, a serious review of which gives a gloomy perspective to future times. Excuse this scrawl, and believe me, with esteem, your humble servant, PATRICK HENRY, JR. JOHN ALOSTP Hudson, N.Y.

HANOVER, Va., Jan. 13, 1773.

DEAR SIR: I take this opportunity to acknowledge the receipt of ANTHONY BENEZETS book against the Slave trade. I thank you for it. It is not a little surprising that Christianity, whose chief excellence consists in softening the human heart, in cherishing and improving its finer feelings, should encourage a practice so totally repugnant to the first impressions of right and wrong. What adds to the wonder is that this abominable practice has been introduced in the most enlightened ages. Times that seem to have pretensions to boast of high improvements in arts, sciences and refined morality, have brought into general use and guarded by many laws a species of violence and tyranny which our more rude and barbarous, but more honest ancestors detested.

Is it not amazing that at a time when the rights of humanity are defined and understood with precision, in a country, above all others, fond of liberty -- that in such an age and such a country we find men professing a religion the most humane, mild, meek, gentle and generous, adopting a principle as repugnant to humanity as it is inconsistent with the Bible and destructive to liberty? Every thinking, honest man rejects it in speculation. How few, in practice, from conscientious motives!

The world, in general, has denied your people a share of its honors; but the wise will ascribe to you a just tribute of virtuous praise for the practice of a train of virtues, among which your disagreement to Slavery will be principally ranked. I cannot out wish well to a people whose system imitate the example of Him whose life was perfect; and, believe me, I shall honor the Quakers for their noble efforts to abolish Slavery. It is equally calculated to promote moral and political good.

Would any one believe that I am master of slaves by my own purchase? I am drawn along by the general inconvenience of living without them. I will not -- I cannot justify it, however culpable my conduct. I will so far pay my devoir to Virtue, as to own the excellence and rectitude of her precepts, and to lament my want of conformity to them. I believe a time will come when an opportunity will be afforded to abolish this lamentable evil. Everything we cam do, is to improve it, if It happens in our day; if not, let us transmit to our descendants, together with our slaves, a pity for their unhappy lot, and an abhorrence of Slavery. If we cannot reduce this wished-for reformation to practice, let us treat the unhappy victims with lenity. It is the furthest advancement we can make toward justice. It is a debt we owe to the purity of our religion, to show that it is at variance with that law which warrants Slavery.

Here is an instance that silent meetings (the scoff of reverend doctors) have done that which learned and elaborate preaching cannot effect; so much preferable are the general dictates of conscience, and a steady attention to its feelings, above the teachings of those men who pretend to have found a better guide. I exhort you to persevere in so worthy a resolution, Some of your people disagree, or at least are lukewarm in the Abolition of Slavery. Many treat the resolution of your meeting with ridicule; and among those who throw ridicule and contempt on it are clergymen whose surest guard against both ridicule and contempt, is a certain act of Assembly.

I know not where to stop. I could say many things on this subject, a serious review of which gives a gloomy perspective to future times. Excuse this scrawl, and believe me, with esteem, your humble servant, PATRICK HENRY, JR. JOHN ALOSTP Hudson, N.Y.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed