| With only two days left in the second trimester before Harlem Academy goes on a two-week spring break, I decided it was a great time to try something new. I have been reading about and intrigued by the concept of a FedEx Day. The idea of a FedEx day originated in the business world as a way to boost creative thinking and problem solving amongst employees. The idea is simple: employees have twenty-four hours to tackle a project that they are passionate about and present their findings to the group. The twenty-four hour time constraint is where the term FedEx Day comes. Companies like Google and Facebook have used this concept to great success as ideas like Gmail and the “Like” button were employee projects delivered in this setting. |

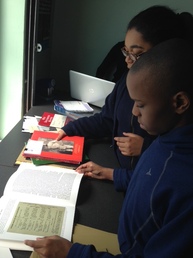

We have internally discussed doing a FedEx day during professional development days at Harlem Academy but so far have not conducted one. It got me to thinking, what would this look like in my eighth grade classroom? Today we’ll find out! My students will have two class periods – FedEx two day shipping, if you will – to research and produce a product that demonstrates their deep understanding of an event or idea from American History of their choosing. With minimal guidelines and scaffolding, this is an opportunity for students to not only research something they are passionate about but also to think creatively about how they can present their work to the class.

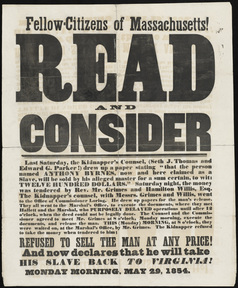

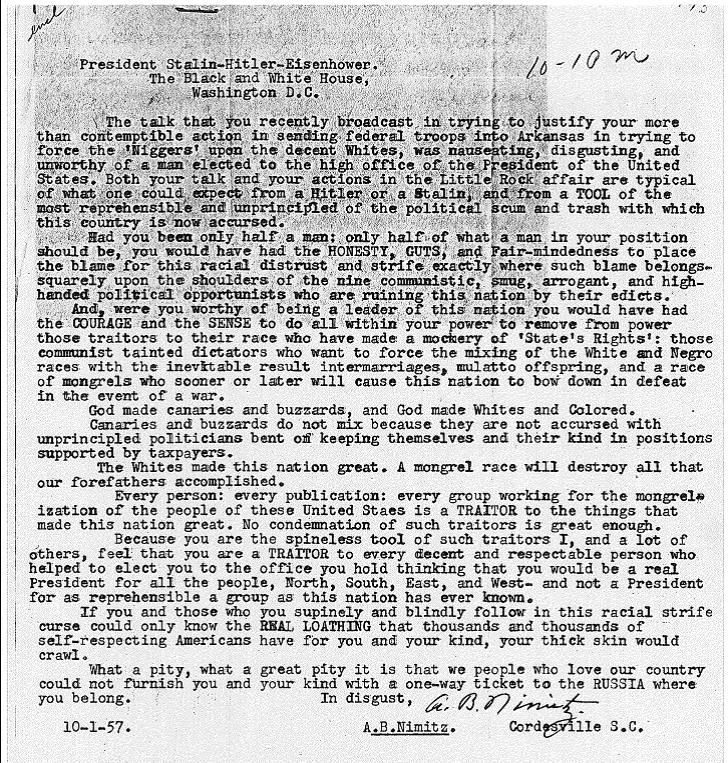

Some of the topics my Junior Historians have chosen to research include: the correlation between the birth of hip-hop in the Bronx and the Harlem Renaissance, the life and work of Congressman John Lewis, the influence the American Revolution had on L’Overture and the Haitian Revolution, the story of Central American immigrants to the United States, H.G. Wells's War of the Worlds, and much more.

After the jump, you can see the directions given to the students. Be sure to check back in April to see my observations about the results and the experience.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed