| Happy 2015! Here at Junior Historians, things have been picking up steam. We have been ramping up our content on this space (as well as on twitter and instagram) and sharing more about how we utilize primary sources in the middle school classroom. We have a lot planned for 2015, so please bookmark our site and make us a part of your online reading routine. This week marked the start of the second trimester at Harlem Academy and the start of two new Junior Historians' Field Manuals. This term the seventh grade will be investigating 19th century US History and the eighth grade will be investigating the Cold War. Let's take a closer look at what's in store ... |

|

0 Comments

The Culminating Project: A New Abolitionist Anthology Reflection:

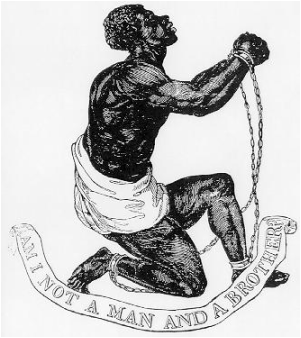

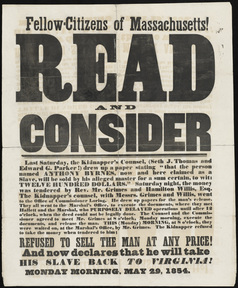

In my seventh grade United States History course we take an entire trimester to investigate slavery in the 19th century. We examine the conditions of chattel slavery, the works of abolitionists, the era of failed compromises, the Civil War, and the Reconstruction Era utilizing only primary source materials. In creating my abolitionism anthology, I intend to create a supplementary workbook for my students to guide them in researching and discussing the evolution of abolitionist writings. In particular, I wish my collection to track the varied justifications and arguments presented by 19th century writers to push the issue of abolitionism to the forefront in the 19th century. The collection will culminate with excerpts from the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln’s second inaugural address, and the text of the thirteenth amendment. Students will then discuss and debate the essential question of whether or not Lincoln deserves the moniker, the Great Emancipator. Students will also identify the argument or justification from the anthology that they feel best exemplifies the abolitionist spirit – in that it is the most persuasive.

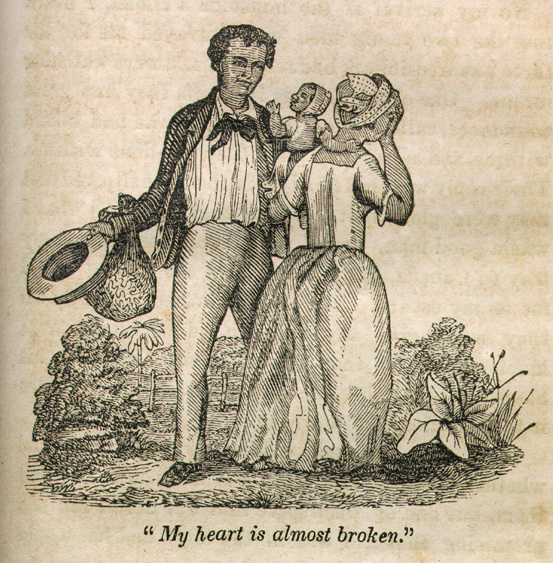

Standout Primary Source: Henry Bibb Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb... Reflection:

When digging for primary sources to include in my classroom, I look for eyewitness accounts that will grab the attention of my students. Though the American Antislavery Writings anthology contains many such sources, the one that stands out as the most historically significant in discussing slavery and abolitionism is that of Henry Bibb. I have used excerpts from Bibb’s autobiography in class before but never the excerpt presented in this course. I found Bibb’s accounts of the slave trade to be historically minded, dispassionate, and very matter of fact. Usually I tend to gravitate towards works that evoke emotion but Bibb’s accounts are so important to understanding the slave trade and does so without sensationalism, that it is hard to ignore. What stands out most is his ability to convey the indignity and inhumanity of the trade by simply retelling the facts – something only a person intimately involved in the trade could do so masterfully. The explanation of the care taken to attract potential bidders and the explicit details of the examinations will help my students understand just how these enslaved people were treated – as cattle or an inanimate object. Particularly of importance is his account of how intelligence is paramount in inspections, that intelligence was seen as a red flag that a slave might be burdensome or arouse trouble on the plantation. This account is not only “sticky” but steers clear of bias or sensationalism that can cloud the discussion of the facts surrounding the slave trade. Honorable mention: Patrick Henry’s letter, James Forten’s pamphlet, and Defoe’s The Life, Adventuress, and Piracies, of … Captain Singleton. One source that I have used for many years in my classroom that should be considered for future iterations of this Amazing Grace course is Susan B. Anthony’s Make the Slave’s Case Our Own speech from 1859. He eloquence is on display in this powerful argument of persuasion. She quotes the scriptures and uses a simple but effective argument. She puts the onus on the listener by humanizing those who have been so dehumanized through the slave trade. By asking her white audience to imagine a slave’s fate as their own and thus compelling us to consider the golden rule by “walking a mile in their shoes.” Undoubtedly no one in the audience would seek to change places with an African American in 1859 but it so succinctly gets at the very moral issue that slavery was.

Putting primary sources into conversation: James Forten’s Letters and the anonymous ballad, The African Slave Reflection:

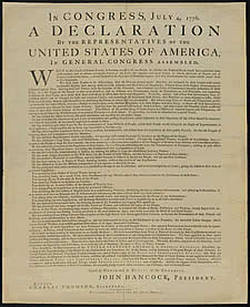

In my 7th grade history class, students investigate the struggle of abolition as a process. From chattel slavery, to the North West Ordinance, the importation ban, the failed compromises, etc, until we arrive at the Reconstruction Era amendments (we pick up the civil rights struggle in the 8th grade). The two texts that best fit into this conversation and illustrate the constant push for abolition and the curious situation of free-blacks in America at the time, are James Forten’s Letters and the anonymous ballad, The African Slave. The first person account of Itaniko’s capture, attempted escape/suicide, role in talking down a rebellion, and mancipation directly to the aversion to and surprise at the actions of these “Christian” men: “You boast of your Freedom … your mild Constitution.” Thus dispelling the philanthropic argument of Christianizing and improving the enslaved African’s lot in life. The eloquence and emotion of the ballad clearly captures well the sufferings of the Africans captured and transported into slavery. The second piece, Forten’s Letters, is a curious continuation of the struggles of Africans in the Americas. Though the slave trade now abolished, Forten speaks of the injustices and inconsistencies in the application of the words of the Constitution. Harkening to the Constitution, Forten says “… declaring ‘all men’ free, they did not particularize white and black, because … [they weren’t supposed to] question whether we were men or not.” Forten here not only exposes the hypocrisies in the document, but illustrates that mere emancipation is not enough to elevate the enslaved peoples to the true status of citizen, or even man. Seeing Pennsylvania as one of the last bastions of liberty for free black men, he laments that the newly proposed bill would render them slaves again – in the stripping of their liberties, movements, and property. These two documents interacting will help my students to see the slow progression towards achieving the ideals in the Constitution through emancipation. That once removed from the bonds of chattel slavery, the free African was no more free in some respects than his enslaved brethren. The long, unsteady march towards full equality would be, as with many things, two steps forward and one step back for many more years to come.  This past fall I participated in Amazing Grace: How Writers Helped End Slavery, a masters level course offered by the Gilder-Lehrman Institute of American History. The course, led by Columbia Professor, and GLI President, James Basker, examined the role of abolitionist writers in the 19th century struggle to end that "peculiar institution." The final project was to compile our own abolitionist writing anthology that could be used in the classroom. I wanted to share the work I generated during this course as perhaps the primary sources I chose could prove useful in your own classrooms. In this blog "mini-series" (Amazing Grace) I will share with you my reflections, my anthology introductions, and the sources themselves. Most, if not all, of the sources I reference can be found in James Basker's book American Antislavery Writings: Colonial Beginnings to Emancipation. Patrick Henry, Letter to John Alsop, 1773Reflection:

One of the major themes and discussion questions that runs throughout my 7th grade American History class is: How have we become a more perfect union? Taken from the Constitution and used as a mission statement for our nation, my students measure the successes and failures of our democratic experiment. The hardest part of introducing this theme to a group of predominantly African American teenagers is the inherent and obvious hypocrisies that existed in the colonial and revolutionary eras. To this end, I found the Patrick Henry letter, Letter to John Alsop, from January 13th, 1773, to be an incredibly unique and insightful document for inclusion in my classroom. Henry is refreshingly candid and open in this letter, not just outlining his practical beliefs on slavery but also clearly and freely admitting to failing to put his ideas into practice. His blunt reflection will be particularly accessible to my middle school students in that they too can relate to believing in one ideal but finding it hard to put that into practice – whether for “general inconvenience” or peer pressure. What I found to be the most significant thing about Henry’s letter was the perspective. He, who was a vocal patriot, could speak of the virtues of liberty and independence but at the same time felt incapable – or perhaps more to the point, unwilling – to extend those ideals to the enslaved Africans. Could he not see clear analogy of the founders and slaves and the king and the colonists? How the king’s tyranny in taxes was in fact less a transgression than the colonists’ tyranny over the body and souls of enslaved peoples? This letter helps to frame two important discussion questions that I engage my students in at this time of study: 1. Did framers consider or debate the extension of rights to more than just white males, and 2. Is there to be sympathy to the king and parliament in the taxation debate? This letter clearly lets my junior historians in on the thought process of how slavery fits into the Enlightened/Revolutionary Era, while also perhaps providing some insight and perspective on how King George might have viewed the colonists. As we wind our way closer to Thanksgiving break and the end of the first trimester at Harlem Academy, my seventh and eighth grade Junior Historians are hard at work on their final assessment of the term. Next week we will be taking final exams, covering all material since September, but today we focus on the American Revolutionary War and the Civil Rights movement in the early 1960s. Both assessments challenge the students to defend a given thesis both by rote and in utilizing a given source document.

Try your hand at a Junior Historians' assessment.

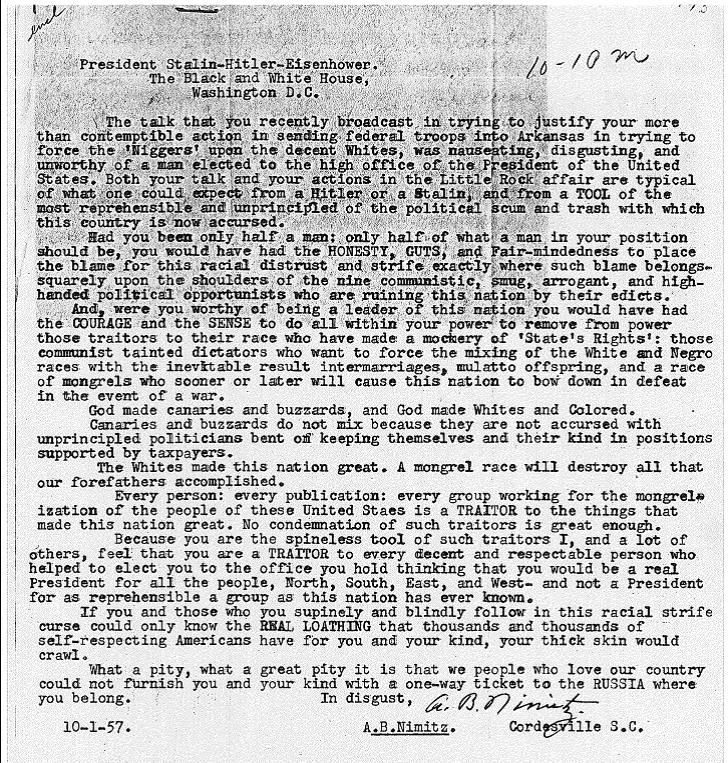

From: www.loc.gov From: www.loc.gov One of the biggest challenges in teaching with primary source documents is vocabulary and complex or dated verbiage. My 7th graders encountered these challenges in reading the text of the Declaration of Independence. The DOI is a brilliantly written argument and one that clearly ranks high in importance in the formation of our nation. It was essential that my students could parse the language and get beyond the pitfalls, to the meat of the document: the logical and evidenced argument for separation from Great Britain. To that end, after summarizing each of the chunked excerpts from the DOI, we created a class "condensed" version of the DOI that put the text into 7th grade friendly language. Below you will find, like a No Fear Shakespeare book, the original text coupled with my class's interpretation of that excerpt in their own language. Enjoy!  From: www.smithsonianmag.com From: www.smithsonianmag.com The hardest part in selecting a primary source is finding one that is engaging, clear, and historically relevant. It's also the most important part of a primary source for the students. A document that can shed light on a perspective that might be hard for students to understand or explain is an invaluable tool in the Senior Historians' arsenal. Today's document is one of my favorites, if not one of the most difficult. A few years ago I participated in a summer seminar through the Gilder-Lehrman Institute that took me to Kansas to study the role of presidential politics in the Civil Rights movement. On one of the days, we were able to visit the Eisenhower Presidential Library and comb through the archives. It was here that I encountered a vitriolic letter written to President Eisenhower in reaction to his handling of the Little Rock Nine crisis in 1957. The blind rage and ignorance is softened by a clear and logical explanation of the author's beliefs. To my knowledge this letter has never been publicly shared outside of my classroom but its potential usefulness in creating dialogue around reactions to Brown and the Little Rock Crisis implore me to share it with the wider historical community. As we read and discuss this in my 8th grade class today, we welcome your reflections, thoughts, and or comments. I will share some of the responses with my students in our wrap-up discussion tomorrow. Without further ado, A Letter to President Eisenhower from a "A.B. Nimitz", 10/1/1957:  From switchboard.nrdc.org From switchboard.nrdc.org It's Friday, which means that it is ASSESSMENT DAY in Mr. Robertson's U.S. History class at Harlem Academy. In the 8th grade we have been examining the legal roots of segregation and its impact on the African American population (particularly in the South) and the nation as a whole. A big focus in this unit was the unequal treatment of African Americans in the armed services and the role of President Truman in sparking the modern civil rights movement. I've attached a copy of today's assessment. Try your luck and see how you stack up against my 8th graders. You can submit your answers to sean@juniorhistorians.com.

etsy.com/shop/birdandbloke etsy.com/shop/birdandbloke Welcome to Junior Historians – so nice to make your acquaintance! Junior Historians is an innovative approach to studying history. I don’t teach history, I teach students how to investigate history for themselves. History can be cumbersome to young students because of the massive scope, complex issues, and our tendency to mythologize our past, particularly our major historical figures. Most US History courses struggle to get past World War II and thus leave students with an outdated view of our nation and the world. By choosing depth, not breadth, of coverage the Junior Historians curriculum unpacks the most important themes of US History up to present day. This fosters an understanding of the role of our shared past – our history – in our current lives. In fact, the Junior Historians’ logo communicates this ideal: a Venn diagram showing the intersection of a specific place and time. The Junior Historians curriculum finally answers the big “so what?” question of history: We study history because it informs the world we live in today and can be an invaluable tool in making decisions about our future. Junior Historians started in 2011 when I was fed up with sub-standard history textbooks and a lack of student understanding and engagement. A life-long history nerd, I tossed out the textbook, developed my own two-year US History course, and compiled my own workbooks utilizing only primary sources. The result – Junior Historians – is a rigorous curriculum that challenges students to take ownership of history and to develop the critical skills of asking good questions, reading, writing, critical thinking, research, and argument by evidence. Check out the new ABOUT and STAY CONNECTED tabs at the top of the page to learn more about Junior Historians. |

Archives

September 2016

Categories

All

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed